A group of companies have placed their bets on clean aviation at Livermore Municipal Airport. They are working to form the nucleus of an electric-aircraft industry hub.

In the past month, electric-powered airplane developer ZeroAvia, Inc., hydrogen producer Apricus Energy Partners Inc., and hydrogen-storage startup Verne, Inc. have all announced plans to begin work at the airport toward hydrogen-electric fuels and electric aircraft.

The viability of the projects depend on the approval of a development proposal submitted last summer to the City of Livermore, which encompasses the three companies’ plans. Apricus Vice President Pete Sandhu said he was providing details to the city to move the proposal along.

Sandhu also owns Five Rivers Aviation, the sole service provider at the airport.

Hydrogen-electric systems, sometimes called fuel cells, combine hydrogen fuel with oxygen from the air to generate the electricity that would power airplane electric motors. The process emits only water. While hydrogen is more weight-efficient than batteries, and can be refueled at about the same speed as fossil fuels, the fuel takes a lot of energy to produce and requires special storage and transport.

Currently, aircraft release about 8% of transportation emissions nationwide, according to the Environmental Protection Agency. Reducing aircraft carbon emissions would help to address climate change.

In a Jan. 22 announcement, Hollister-based ZeroAvia said it will begin its Livermore work at the airport building liquid-hydrogen refueling trucks, which will provide the speed and capacity needed to compete with conventional jet-fuel refills.

“Given the gravity of the climate emergency, the rapid acceleration of clean engine technology (for airplanes) using fuel cells must be met with optimized refueling technologies and infrastructure to ensure speedy adoption,” said ZeroAvia Founder and CEO Val Miftakhov in a statement.

In time, the company will also work on research and development for their aircraft, engines and fuel trucks at Livermore, said Sandhu.

“They’re planning a pretty heavy presence and a lot of jobs here in Livermore,” said Sandhu, who added that ZeroAvia began work in Livermore late last year.

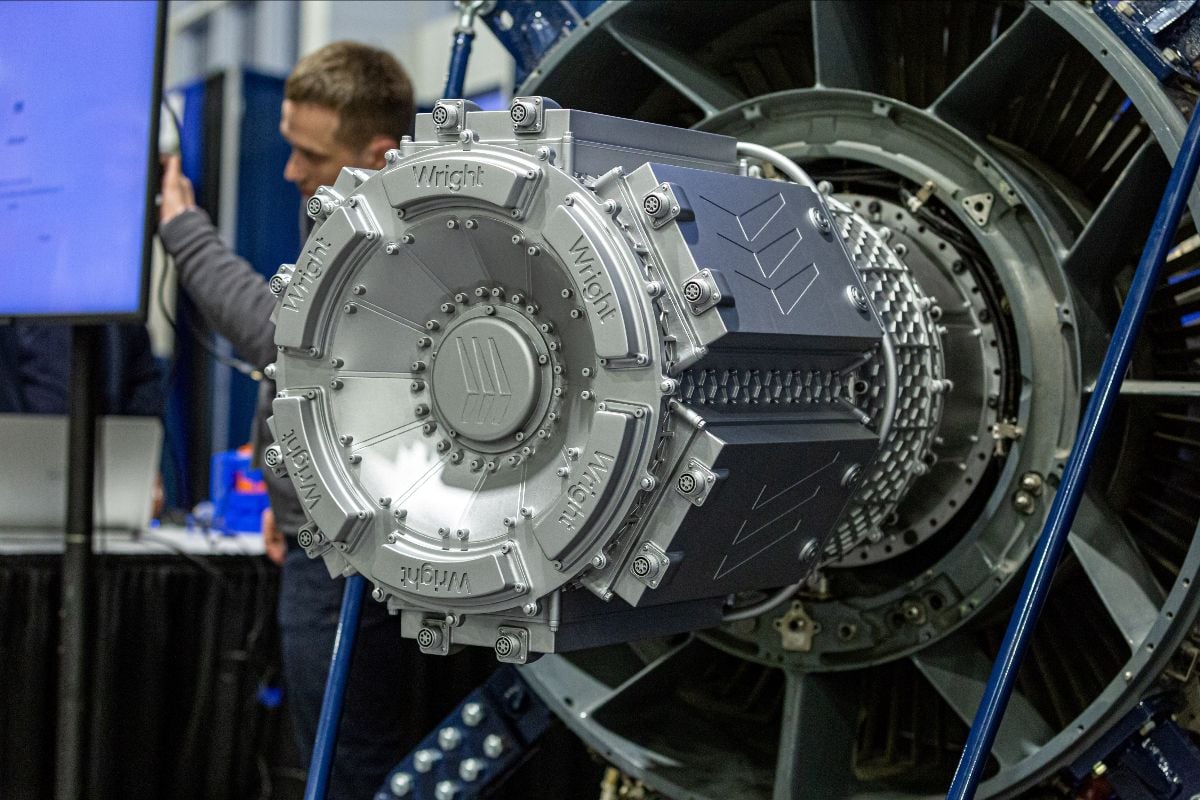

ZeroAvia aims to sell a 19-seat, hydrogen-electric airliner with a range of 300 miles by the end of next year, and one with up to 80 seats and a 700-mile range by 2027. One of its engines made history by powering the test flight of a 19-seat airliner last year, the largest aircraft flown using hydrogen-electric propulsion at the time.

Meanwhile, Livermore-based Apricus envisions building some 140 acres of solar panels on Livermore airport land. The small power plant would use reclaimed water to produce zero-carbon hydrogen without adding demand to the area’s potable water.

Apricus CEO Sean Boyd estimates production to begin by the middle of 2026.

“Our proposal to the city aligns with their sustainability and carbon-reduction goals,” said Boyd. “It aligns with California’s clean energy goals. We are committed to helping sustainability in these areas. We want these areas to grow and develop using clean hydrogen. Rather than it be built in other states or in other jurisdictions, you can build it right in your backyard and use it in your backyard.”

Berkeley-based Verne, in partnership with the Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory, demonstrated a hydrogen-storage system large enough for heavy-duty use, such as refueling semi-trucks, late last year. It will work with ZeroAvia at compressing cold hydrogen to extend aircraft ranges.

Sandhu also expects further hydrogen demand from the Livermore Amador Valley Transit Authority, which has included hydrogen fuel-cell buses in its plans for zero-emission bus purchases by 2029.

But electric aviation remains in its early stages. Federal certifications must be acquired before the new electric technologies can fly passengers. Large, all-electric commercial aircraft might not become viable for decades, according to one National Academies of Sciences study.

“They can develop fuels all day long,” said one anonymous pilot based at Livermore. “At the end of the day, nobody will build a fuel pump for a fuel that doesn’t exist into airplanes that don’t exist.”

While solar hydrogen sidesteps many problems facing battery-electric aircraft – slow charge times, too much demand on the power grid, and overheated batteries – Sandhu recognized the overall chicken-and-egg problem with electric aircraft and the infrastructure needed to support them.

Unphased, he said, “We want to just get ahead of it, because we are confident that the demand’s going to be there.”